Summary

One Christmas, the cruelty of my isolation was laid bare in the most harrowing way. My body was a canvas of oozing sores and open wounds, the result of constant and severe sunburns that had gone untreated. These painful lesions dotted my face, scalp, hands, and legs, exuding a putrid odor that attracted swarms of buzzing flies. To the ignorant eyes of those around me, these wounds were mistaken for a contagious disease, fueling their misguided fear and revulsion.

“Sherleen, You Have Albinism”

It took me twenty-five years to utter those words to myself, a profound realization that came after a poignant phone conversation with Ducton, my elder brother. His gentle reminder unlocked memories I had subconsciously barricaded, a coping mechanism against the cruelties of a world that had ostracized me for being different.

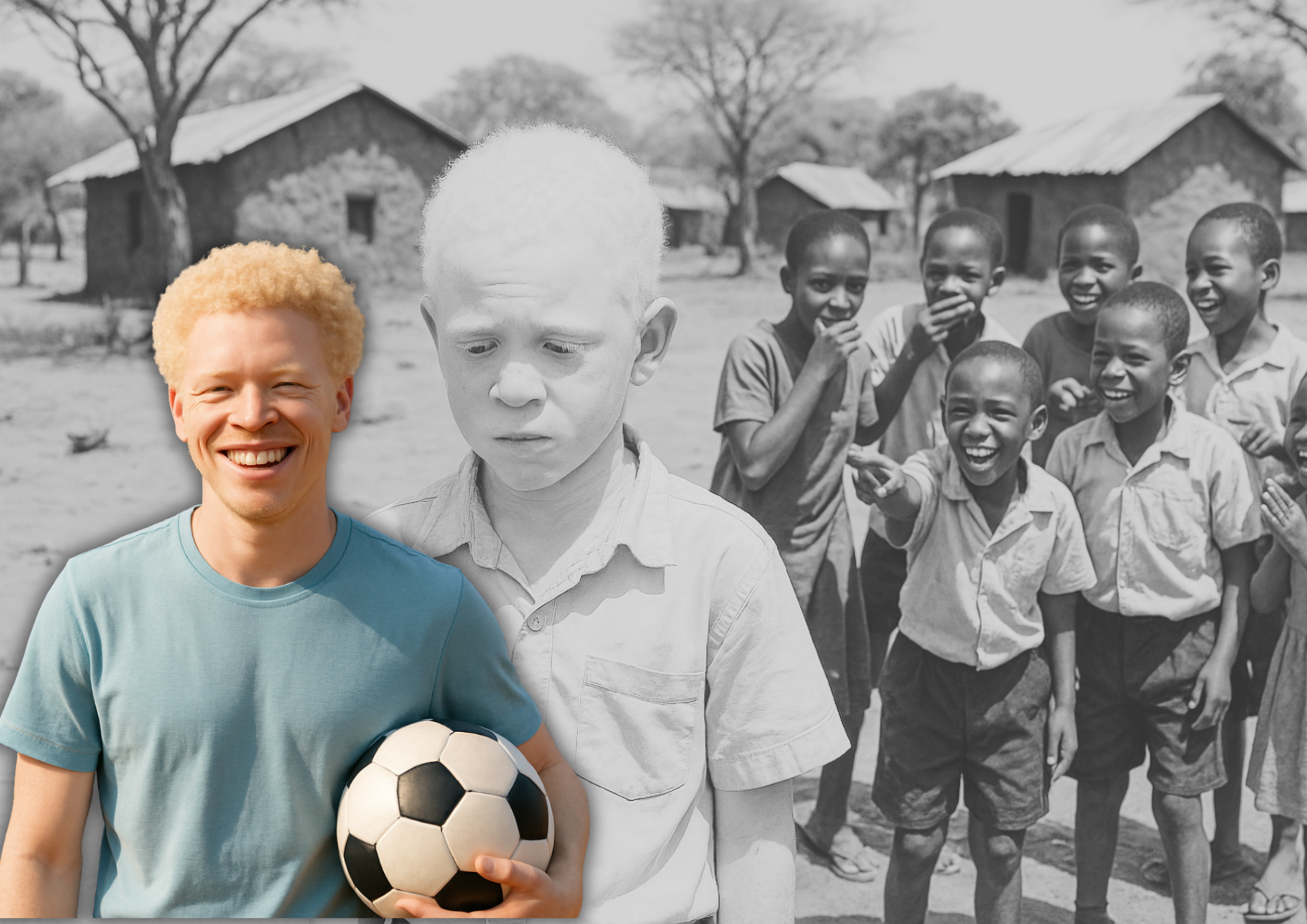

A Childhood of Loneliness and Taunts

As a child, loneliness was my constant companion. Whenever I ventured out, a chorus of jeers would trail behind me, cruel voices shouting mzungu (white girl), muindi (Indian), or jini (ghost). But the statement that never failed to bring tears to my eyes was the callous declaration: “Kujeni muone! Hii ni nini? Hii si mtu.” (Come and see, what this is. This thing is not human!) In self-defense, I carried a long stick, ready to strike at anyone who dared to chase me while hurling insults, earning myself a reputation as an aggressive, animal-like creature.

Friendships eluded me, as children excluded me from their playdates, and I lived in constant fear of rejection. Even my own siblings were embarrassed to be seen with me, making excuses to leave me behind, while taking our youngest sibling along without a second thought.

The Painful Memories of Christmas

One Christmas, the cruelty of my isolation was laid bare in the most harrowing way. My body was a canvas of oozing sores and open wounds, the result of constant and severe sunburns that had gone untreated. These painful lesions dotted my face, scalp, hands, and legs, exuding a putrid odor that attracted swarms of buzzing flies. To the ignorant eyes of those around me, these wounds were mistaken for a contagious disease, fueling their misguided fear and revulsion.

Banished from the family celebrations, I found myself confined to the chicken pen, forced to endure the stench and the incessant torment of the flies alone. At eight years old, I had grown accustomed to being treated as something less than human, an outcast in my own home, simply for the crime of being different. As the joyous laughter of my family echoed in the distance, I sat in silence, tending to my agonizing wounds and wondering what transgression had cursed me to such a wretched existence.

A Father’s Fanciful Tale and a Budding Creativity

Desperate for answers, for any shred of understanding that could make sense of my plight, I once asked my father why I was so different from the rest of our family. His response was a fanciful tale, a whimsical fiction spun to shield a child’s heart from the harsh realities of the world: “Oh, I purchased you in London. The pilot dropped you at the market, and I picked you up there. That’s why you are my white girl.” For years, I clung to this story, a fragile illusion that offered solace in its fantastical explanation for my stark dissimilarity.

To many, Barbie dolls represent unrealistic beauty standards, stereotypical gender roles, a lack of diversity, and the embodiment of materialism. But for me, they held an entirely different significance. When my father began bringing them home, I beheld physical manifestations of my uniqueness, dolls that finally resembled me, their fair skin and hair mirroring my own albinism. Though their outfits were boring and uninspired, these plastic companions ignited a spark within me, a love for fashion and creativity that had been lying dormant, yearning for expression.

I found solace in designing and hand-stitching clothes for my Barbies, breathing life and individuality into these once-generic figures. Each stitch was a stroke of defiance against the narrow definitions of beauty and identity that had ostracized me for so long. These dolls became my confidants, my muses, as I poured my yearnings and aspirations into the garments I meticulously crafted for them. This creative outlet soon extended to repurposing my siblings’ hand-me-down dresses, cutting them apart and sewing them back together in unique, more interesting ways that reflected my burgeoning sense of style and self-expression.

To the world, these dolls may have represented conformity and shallow ideals, but to me, they were the catalysts that unleashed a wellspring of artistry and self-acceptance, the first steps on a journey of embracing my true, authentic self.

The Threat of Violence and a Sanctuary

In 2010, the world was rocked by horrific news of attacks, kidnappings, and killings of people with albinism for their body parts – a grisly trade that saw our organs, hair, nails, and limbs fetching exorbitant prices, primarily in Tanzania. The revelation was a brutal awakening, a stark reminder that my very existence was seen as a commodity by some, a prize to be harvested for profit.

The threats felt all too real, whispers of being “sold to Tanzania” echoing in the shadows, taunting me with the possibility of becoming another statistic in this macabre industry. Even today, the trauma lingers, with strangers casually referring to me as “money,” their cruel jokes cutting deep: “Why are you broke when you are money? Just sell yourself and pay your bills.” Each jeer, each callous remark, rips open old wounds, forcing me to relive the terror of those dark days.

My father, fearing for my safety, confined me to the house or school, desperate to shield me from those who saw me as little more than a commodity to be traded. After primary school, a family member suggested I attend a school for the blind, a sanctuary where I could be among “my kind” – a place where, for the first time, I encountered others like me, people with albinism whose fair features mirrored my own.

It was there that I experienced a profound shift, a sense of belonging that had eluded me for so long. And when I laid eyes on a boy with the same condition, something awakened within me – the first flutters of romantic love, a feeling I had long thought denied to someone like me. In that moment, amidst the safety of those familiar faces, I caught a glimpse of what it meant to be truly seen, to be accepted for who I was, without fear or judgment.

Highs and Lows of Education

High school offered a respite, as I finally found a place where I could blend in without enduring taunts or having my blood inspected for the color of a “monster.” Yet, I was shocked to witness albino classmates suffering from painful skin conditions, some even forced to leave school due to severe cases of skin cancer.

University life brought new challenges. My foray into campus politics was met with cyber-bullying, with cruel insults likening me to a “skinned pig.” Unable to cope with the hostility, I abandoned my political aspirations. Instead, my friends and I designed t-shirts to raise awareness about albinism, a small act of defiance against the ignorance that had plagued my life.

The Pursuit of Passion and Acceptance

When my sister suggested modeling as a career path, I was met with designers who treated my condition as if it were contagious. Undeterred, I returned to my first love – designing and creating my own clothes, a passion that had blossomed from those early days of dressing Barbie dolls.

Through my experiences, I’ve come to understand that many people with albinism grow up in isolation, living in fear of rejection and hesitant to pursue their dreams for fear of failure. Most of us, myself included, have refused to accept their condition, preaching acceptance and inclusivity while denying the very essence of who they are. It is only through true self-acceptance that we can shed the shackles of denial and embrace our authentic selves, flaws and all.

0 Comments